Details

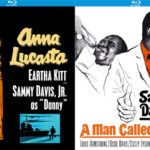

One of the lesser-known stories from Sammy Davis, Jr.’s career is how he shot a TV pilot for a 30-minute sitcom on network television in 1953 – at the time, an inconceivable achievement for a black entertainer. But, the times being what they were, the show never saw the light of day.

In February 1953, Leonard Goldenson, the President of United Paramount Theatres (Paramount Pictures’ movie theatre chain), orchestrated a merger with the then-failing television network ABC. Goldenson knew that ABC needed new fresh talent and quickly (its top show, The Lone Ranger, was rating a lowly #29). Since 1938, Goldenson had used the William Morris Agency to book stage acts to entertain audiences between movies, and so unsurprisingly he turned to Abe Lastfogel of William Morris for help.

Most television entertainment in 1953 was broadcast live – but the success of I Love Lucy (by 1953, the #1 show by Nielsen ratings) indicated that filmed sitcoms had a future. With this in mind, Lastfogel suggested shows be developed around Ray Bolger, Danny Thomas, George Jessel, and Sammy Davis, Jr. Lastfogel had signed Sammy to the William Morris Agency after The Will Mastin Trio’s famous opening at Ciro’s in March 1951, and he knew that Sammy was desperate to get into television.

While several black entertainers had previously starred in short-lived variety series across various networks, the only sitcom at the time featuring black performers was Amos ’n’ Andy, a comedy spinoff from the radio show of the same name. Featuring an intensely demeaning and stereotypical portrayal of Negro culture, the show had plenty of admirers (including Sammy), but also plenty of critics. The NAACP mounted a long campaign to have the show cancelled, and they succeeded in April 1953.

Groundbreaking TV pilot

Could a show starring a Negro, who was not a maid, servant, or insulting caricature, be successful in 1953? Sammy would soon find out. In July, ABC signed Sammy to a $150,000 contract, and put $20,000 into the production of a pilot show – and the announcement was reported with much excitement in the black press. However, in September and October 1953, the shows ABC had built around Ray Bolger (Where’s Raymond?) and Danny Thomas (Make Room For Daddy) premiered, but there was no sign of Sammy’s show; getting the pilot made was an eight-month process.

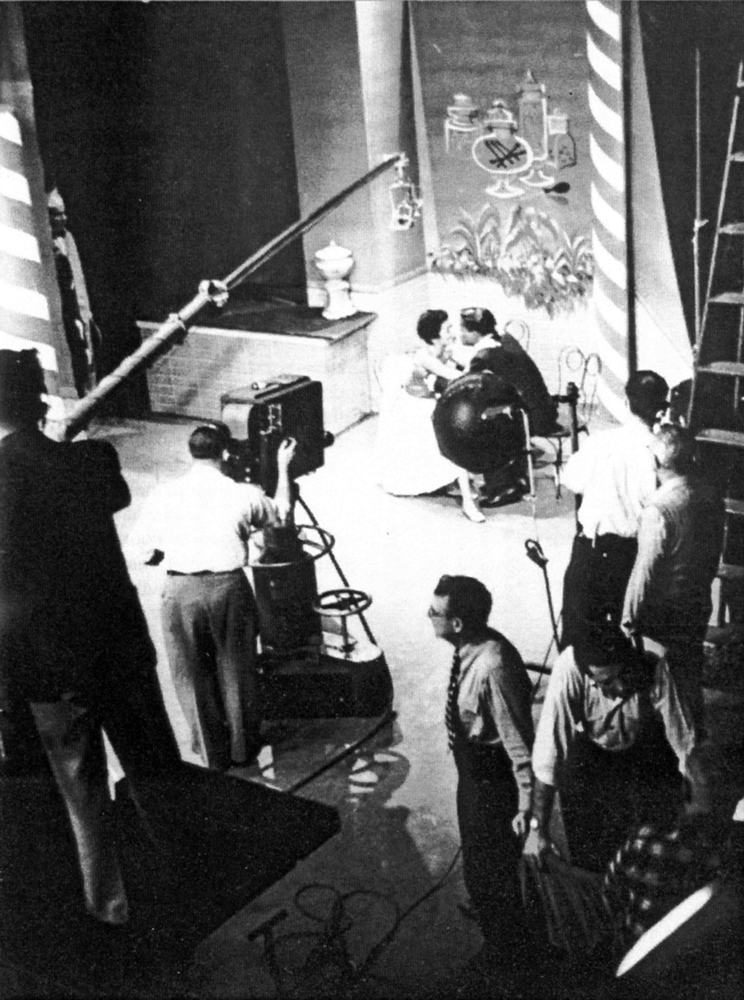

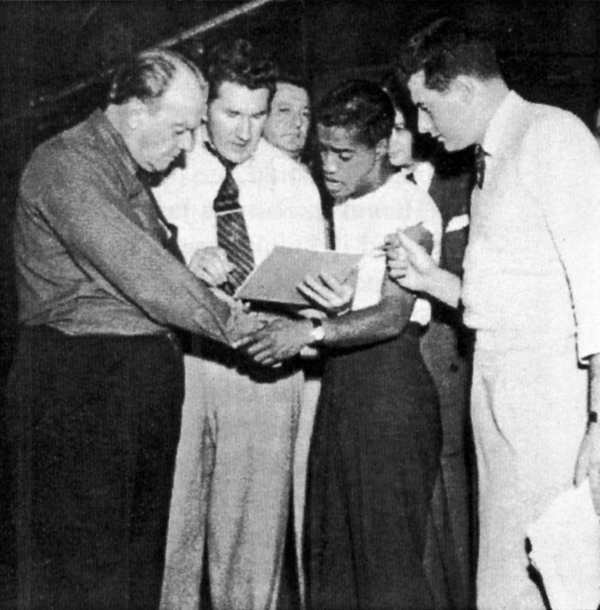

Three years before Sammy would hit Broadway in a musical using a similar conceit, the plan for the sitcom was to showcase Sammy’s many talents by having him, his father (Sam Sr.) and Will Mastin star as a family of nightclub performers, named the Lightfoots. (Playing themselves was the safest bet for Sam Sr. and Will, neither of whom were actors. They couldn’t remember their lines or hit marks, and hated the very notion of television. But if ABC wanted Sammy Davis, Jr., ABC had to have The Will Mastin Trio.)

Cast as Sammy’s girlfriend was dancer Frances Taylor, the future Mrs. Miles Davis, whom Sammy remembered from Ciro’s nightclub where she had danced with the famed Katherine Dunham Company. Also cast in supporting roles were Frederick O’Neal (co-founder of the American Negro Theater, graduates of which included Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte) and Ruth Attaway (who would later appear in Porgy and Bess with Sammy).

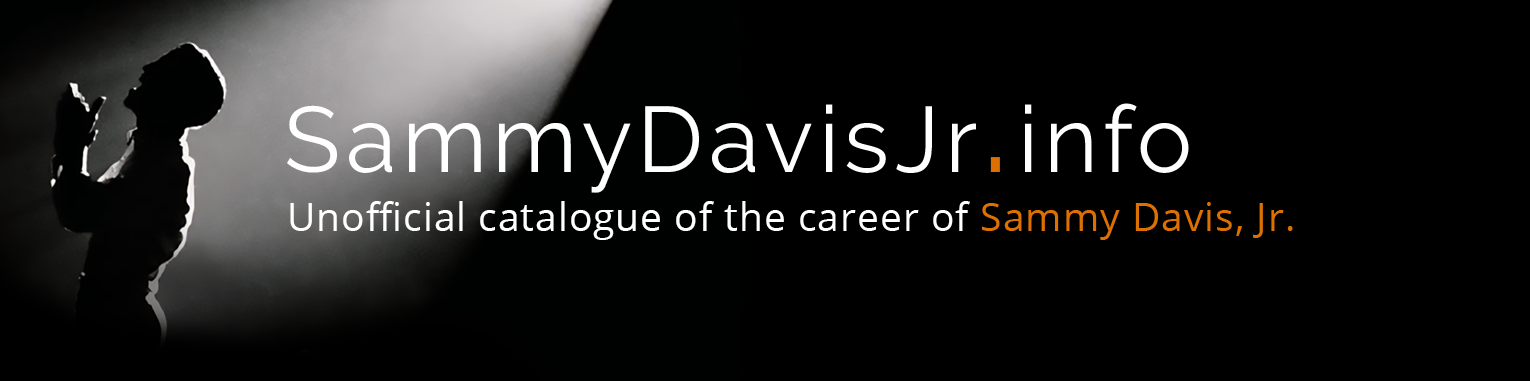

Behind the scenes, choreographer Hal Loman worked with Sammy and a chorus line of dancers (both black and white, making the production an integrated one), while Sammy’s business partner Arthur Silber, Jr. and his publicist Jess Rand worked with the producers. The show had comedy, music, and dance numbers, but also some heartfelt drama. When the pilot was finally shot in early 1954, it was taped before a live studio audience. At its conclusion, the whole production felt they had achieved something both groundbreaking and artistically worthwhile.

No corporate sponsorship

The network took the pilot, initially titled We Three (or Three For The Road, accounts differ), and started to look for a sponsor. At the time, most television shows were funded by a single corporate sponsor, and ABC could find no company interested. With nothing announced by April, ABC’s Vice President of Programming and Talent, Robert Weitman, was forced to publicly dispel rumours that southern advertisers and affiliate stations were refusing to support a show with a black lead. But he also suggested the show was now being planned as an “all-Negro” production, and that this might make it more palatable to a southern audience than if the cast remained integrated. This confirmed, in part, suspicions as to why the show was failing to sell in the first place.

In September 1954, ABC announced it was renewing Sammy’s contract and that it still had faith that the program, now officially titled Three’s Company, would air that year. But in October, the fall television season started without a sponsor willing to support the show and it was officially dropped. ABC had caved to the power of the south – three years before Nat King Cole’s variety show on NBC would famously struggle and eventually finish for identical reasons.

In retrospect, it was amazing that a network would fund such a pilot in the first place. Sammy’s talent was undeniable, but America was seemingly not yet ready for a black man to be portrayed on television in an independent or affirming fashion.