Golden Boy (Broadway) |

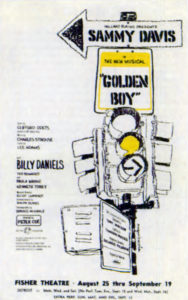

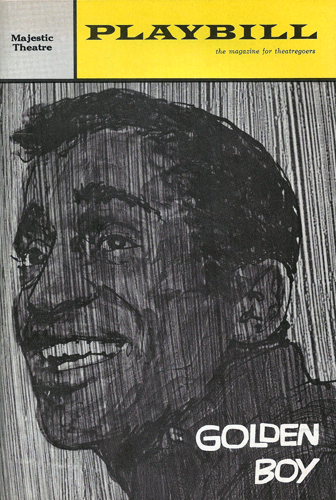

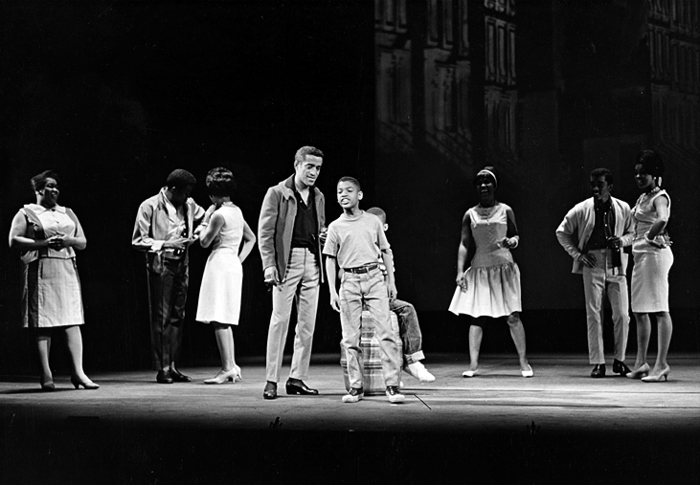

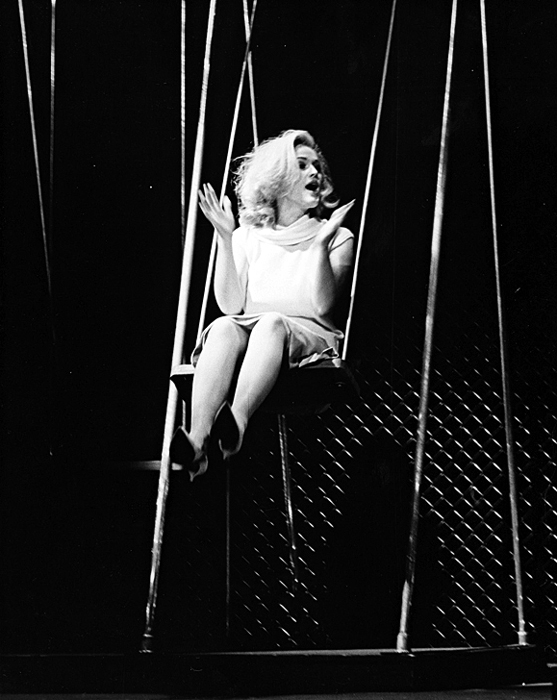

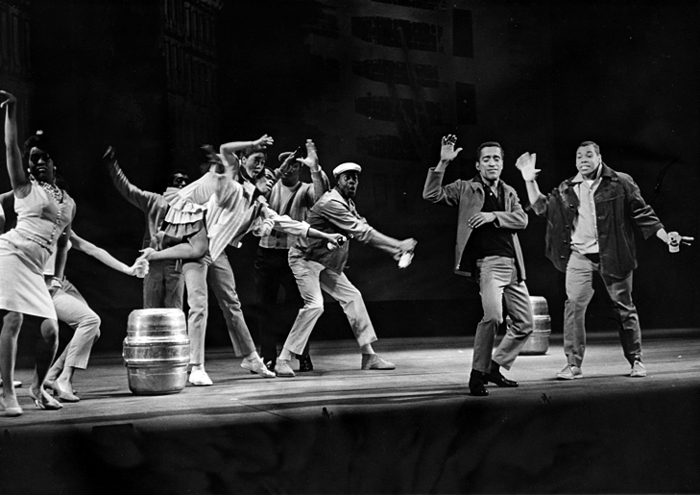

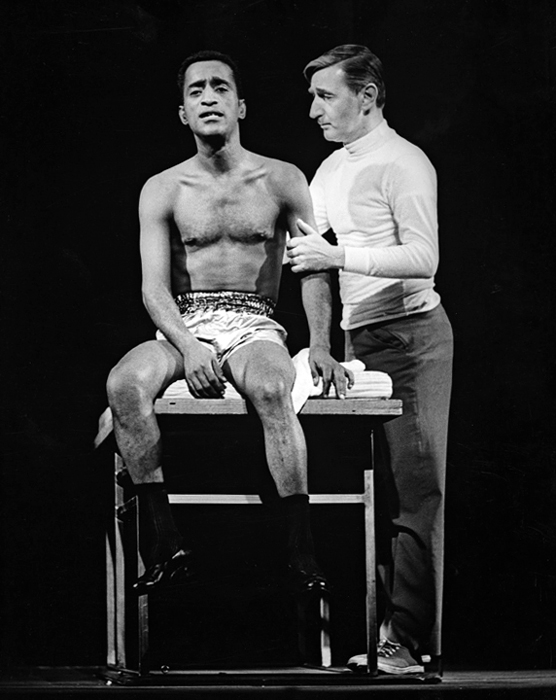

| Opening Date: 20 October, 1964 / Closing Date: 5 March, 1966 Performances: 569 performances Venue: Majestic Theatre, New York Producer: Hillard Elkins / Director: Arthur Penn Cast: Sammy Davis, Jr., Paula Wayne, Billy Daniels, Ted Beniades, Kenneth Tobey, Roy Glenn, Johnny Brown, Charles Welch, Jeannette DuBois, Louis Gossett, Jaime Rogers. Book: William Gibson and Clifford Odets Music and Lyrics: Charles Strouse and Lee Adams Musical Director: Elliot Lawrence Tryouts: Shubert Theatre, Philadelphia – 25 June to 25 July, 1964 Shubert Theatre, Boston – 28 July to 22 August, 1964 Fisher Theater, Detroit – 25 August to 29 September, 1964 |

Details

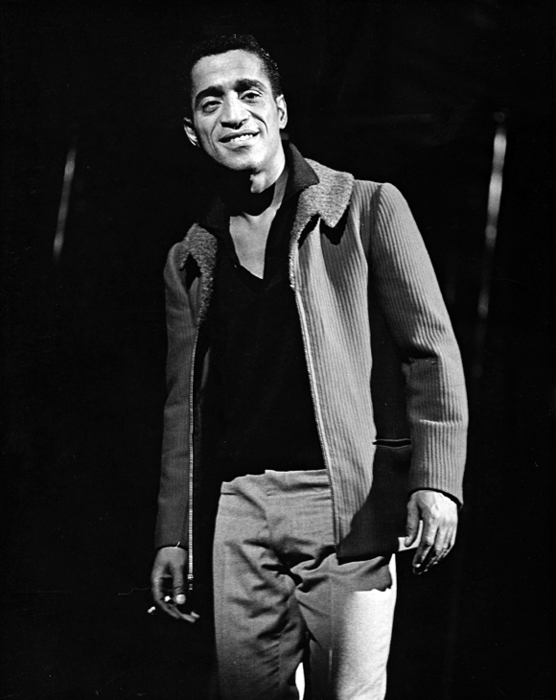

A project which would play a significant role of the life of Sammy Davis, Jr. for seven years was born when producer Hillard Elkins saw Sammy performing at a ‘midnight matinee’ in London at the Prince of Wales Theatre in September 1961. In Sammy’s dressing room after the show Elkins implored him to return to Broadway (Sammy had starred in Mr. Wonderful in 1956). Elkins suggested he had the right vehicle: Golden Boy, the tremendously successful 1937 stage play written by Clifford Odets. The play was about an Italian-American concert violinist, Joe Bonaparte, who turns to boxing. It had subsequently been made into a film starring William Holden, in his film debut. Featuring a tragic death in the ring, it was a serious work exploring the immigrant experience and the machinations of the boxing world. Sammy was interested.

Elkins began a two-year process of bringing his idea to fruition. He met with Odets and obtained not only his permission to adapt the play, but also Odet’s agreement to write the book for the musical adaption himself. Elkins and Sammy envisioned a racial equality angle to replace the immigrant/class themes in the original. Elkins secured the services of composer Charles Strouse and lyricist Lee Adams (who had impressed with their score for Bye, Bye Birdie) to write the music. Although Sammy had not officially signed on, the two writers followed Sammy around the country testing jingles, songs and ideas, to see what would work for him.

Strouse told Sammy biographer Wil Haygood “The goal was so magical … there were a couple years we worked with him, but there was always in the back of my mind the nightmare he wouldn’t do it”. Financially, the theatre was a poor option for Sammy, who was clearing around $40,000 per week on the road. His salary would drop to around $20,000 per week on Broadway. Although this would make him the highest paid performer in Broadway history, Sammy was still splitting his income three equal ways, between himself, his father Sam Sr., and Will Mastin, despite the fact both Sam and Will were now retired. This left him with around $7,000 per week – barely enough to keep up with his profligate lifestyle.

However, the potential for critical success on the stage to lead to further film roles was particularly attractive, and the prospect of ceasing to tour and building a home life in one location (and spending more time with his two children) was of great importance to his wife, May Britt. In addition, Sammy felt he had unfinished business on the stage given his disappointment with the creative aspects of Mr. Wonderful. Golden Boy would be different: “Mr. Wonderful was just a series of jokes and songs … certainly nothing like Odets”, Sammy said. Eventually, he signed on.

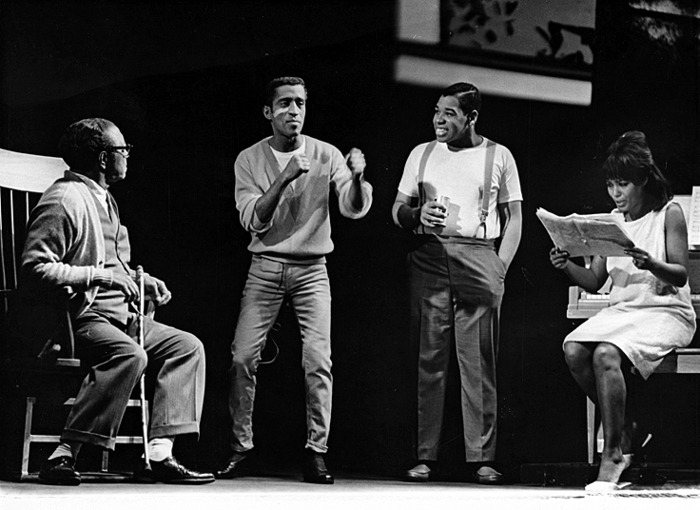

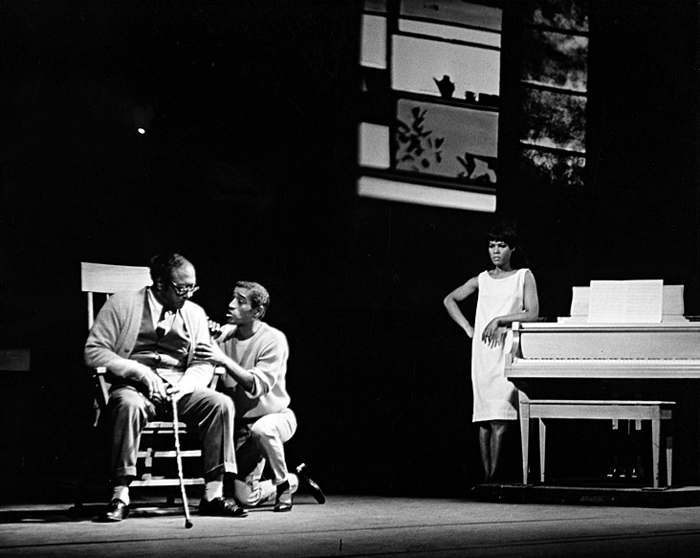

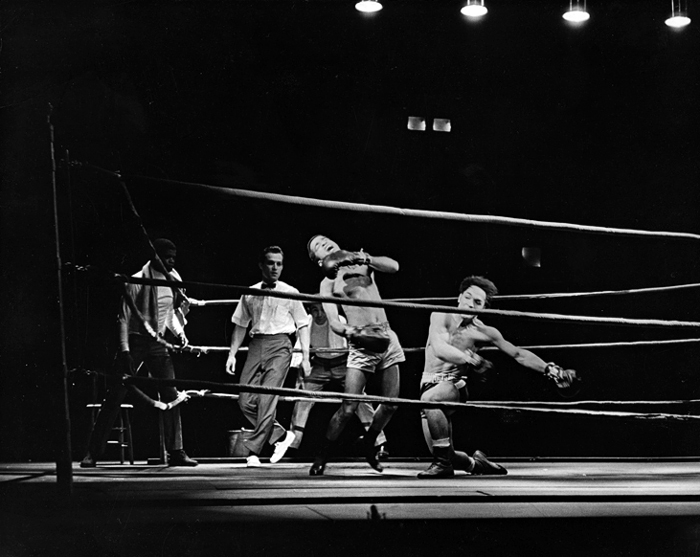

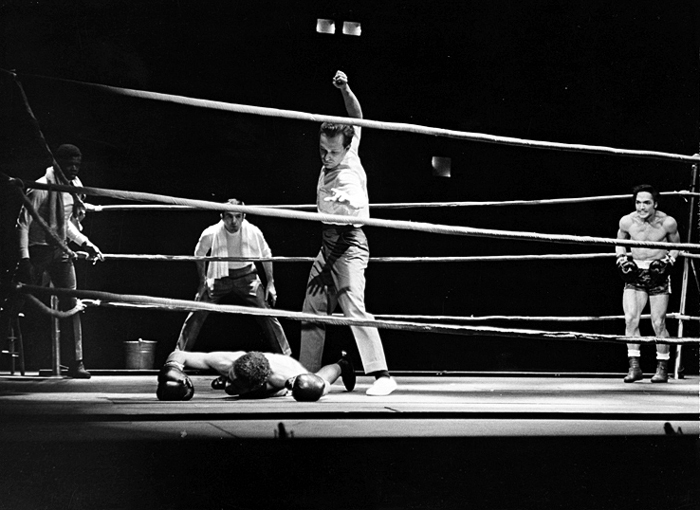

Meanwhile, Odets had proved particularly tardy in providing his adaption. A reluctant flyer, he finally saw Sammy Davis, Jr. perform in person in Philadelphia and this provided a brief burst of enthusiasm (telling Sammy “I’m going to write this play in your mouth!”), but it did not last. By the time rehearsals began in New York, on 15th May, 1964, Odets had completed only two drafts, and there was significant work left to be done. While Sugar Ray Robinson assisted the production in staging the boxing scenes realistically, Odets returned to California to work on the book. However, he soon became ill, and in late July he was hospitalised. His doctors quickly realised he had cancer, and he died on 14th August.

Tryouts

By this stage tryouts had begun at the Shubert Theater in Philadelphia. Fortunately, Hilly Elkins and Sammy had agreed upon a relatively long try-out period on the road before opening in New York, Sammy saying at the time “I don’t go for the unfairness of all those last-minute switches in shows. It’s not going to happen to me … I’m just saying you’ve gotta give yourself enough time to straighten out your problems.” He had no idea what he was in for.

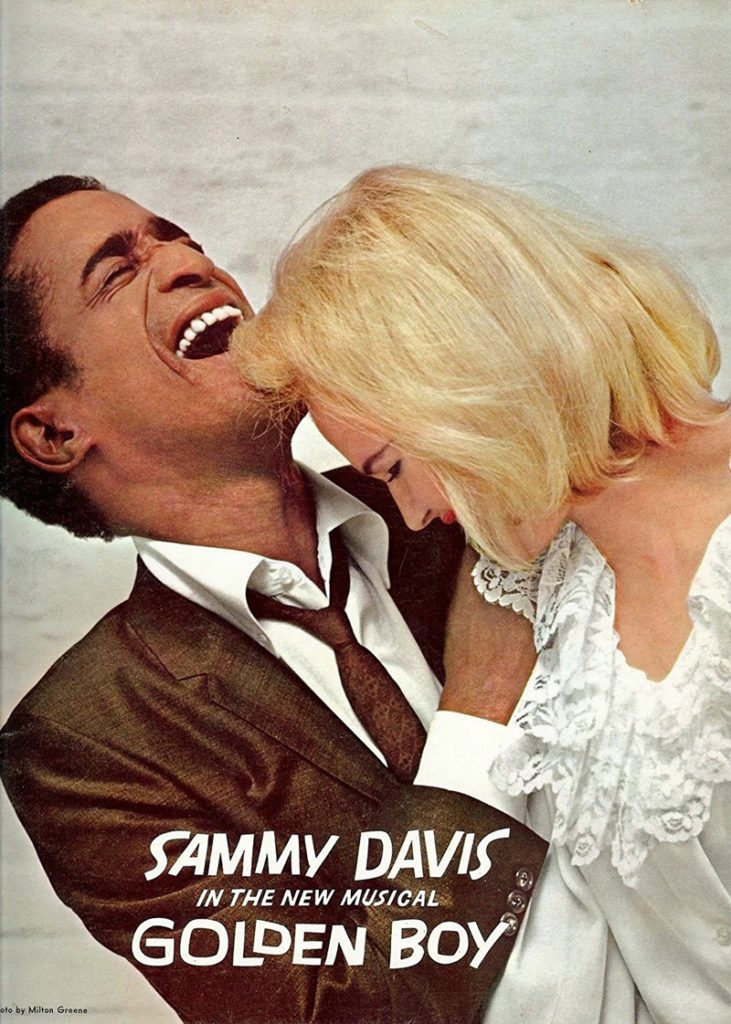

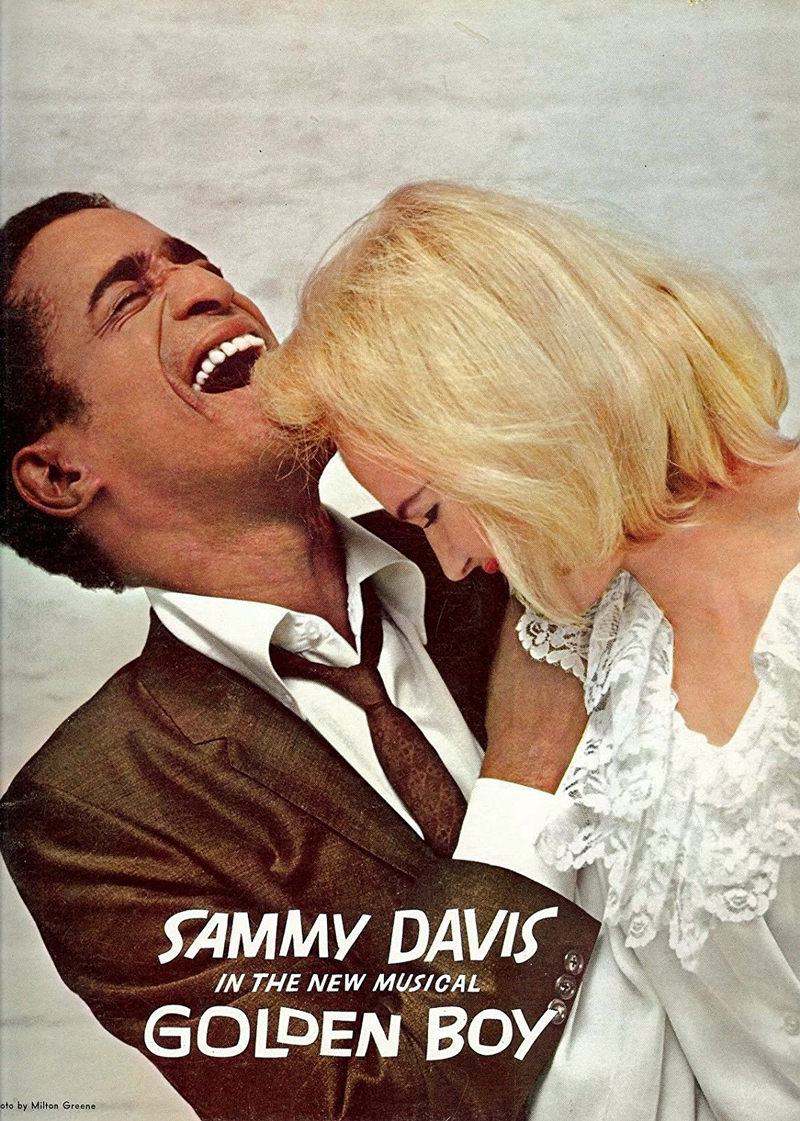

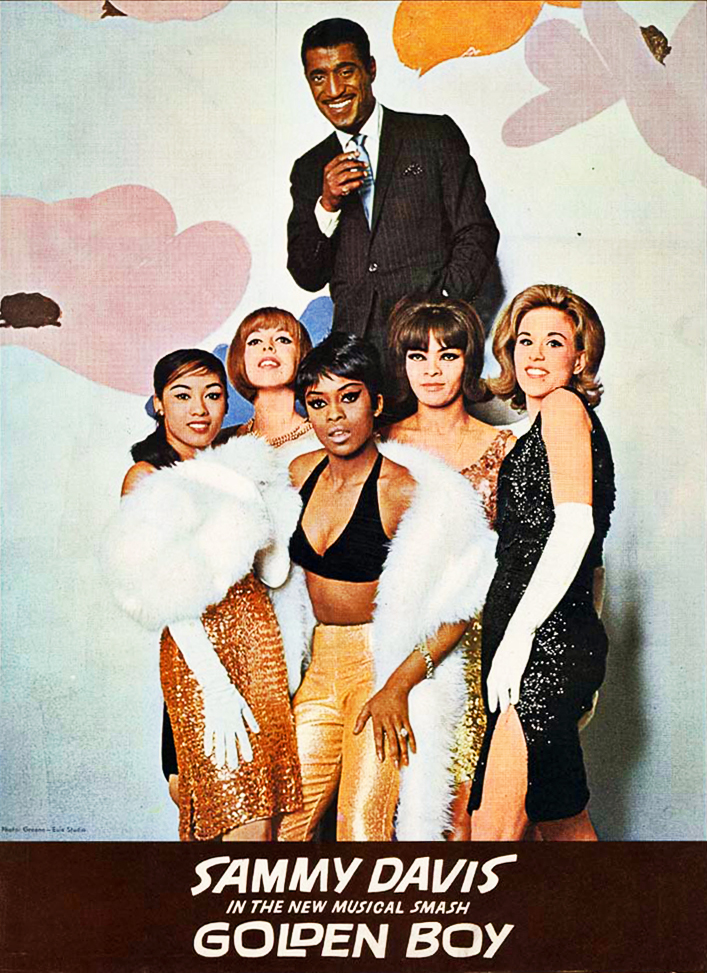

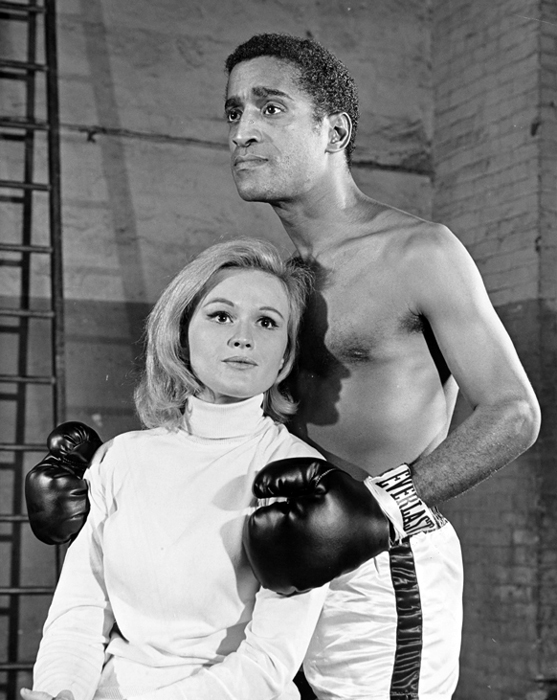

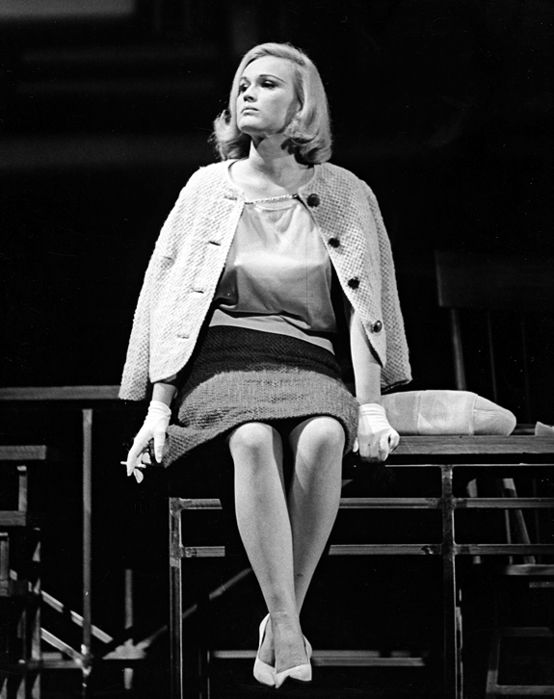

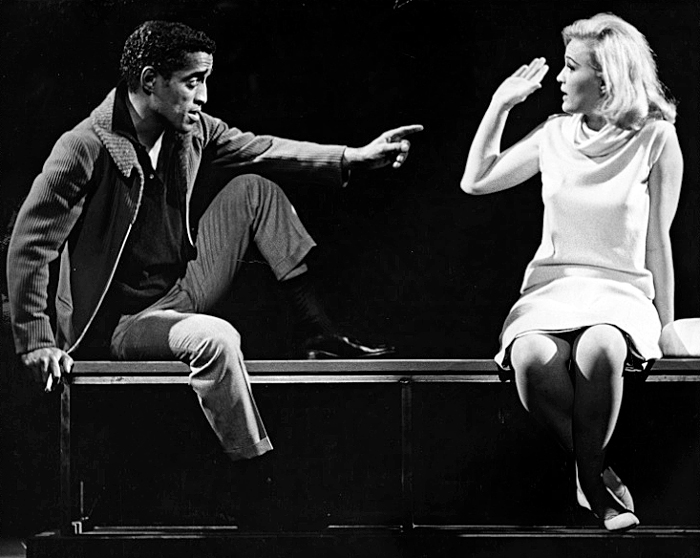

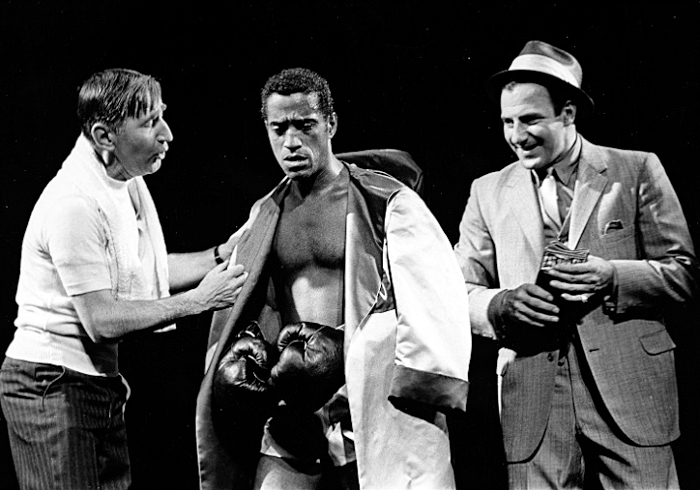

Englishman Peter Coe was employed to direct, having previously directed Oliver! on Broadway. Nightclub singer Billy Daniels came in to play Eddie Satin, a slick boxing promoter with whom Joe would make a Faustian bargain. Paula Wayne was cast as Lorna, the white love interest of Sammy’s character Joe (now renamed, somewhat wittily, Joe Wellington from Joe Bonaparte). Lola Falana was later cast in the ensemble of dancers … and she quickly caught Sammy’s eye.

With an unfinished book, the reaction from the Philadelphia critics was mixed, and changes had to be made. Elkins, Coe and Davis found themselves writing and re-writing dialogue on the fly. Strouse and Adams likewise struggled with the score: songs were thrown out, others were added. Despite the fact Sammy had already recorded them for Reprise back in April, “There’s A Party Going On” and “Yes I Can” were two of ten songs cut as the production moved to Boston. Further changes in Boston saw Joe become first a pianist, then a surgeon afraid to punch too hard lest he damage his hands (and not be able to save the lives of blacks turned away by racist white surgeons). Amongst the chaos, Coe and Sammy found they couldn’t work together and reportedly even came to blows.

Desperate for assistance with the book, Elkins turned to Clifford Odets’s friend, playwright William Gibson. As a tribute to his former mentor, Gibson embraced the challenge and set to re-writing everything – focussing more on the interracial romance, Joe’s ambition to escape Harlem, and the general plight of the black community. The subplot concerning Joe’s occupational struggles was eliminated entirely. Peter Coe, who was unreceptive to Gibson’s ideas, found himself summarily fired by Elkins, and he was swiftly replaced as director by Gibson’s close friend Arthur Penn.

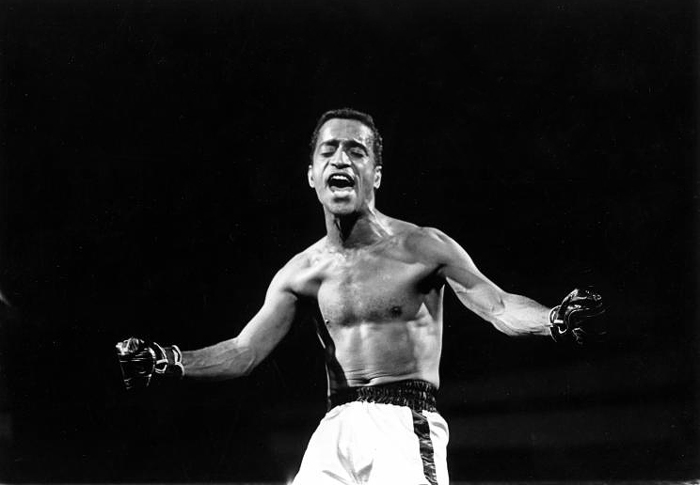

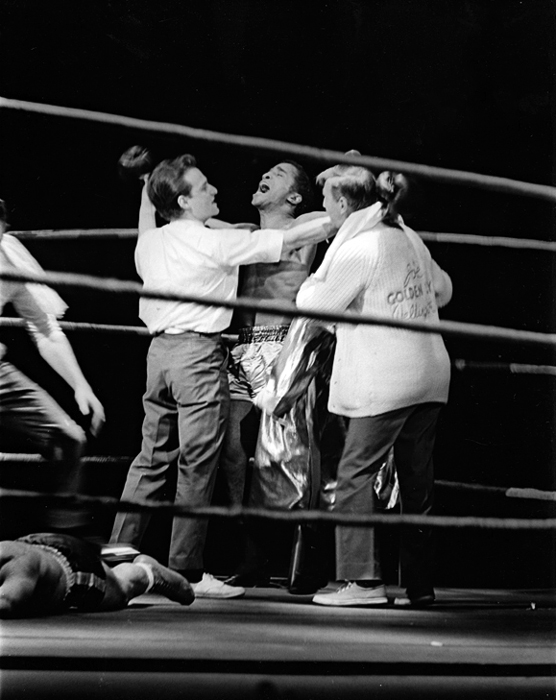

Sammy encouraged Gibson to “write coloured”, and with Gibson and Penn working together, the civil rights element of the show came into sharper focus: Joe (who boxes against his father’s wishes) is promised a life free of the ghetto by an unscrupulous black promoter, Eddie Satin. Satin starts to take control of Joe’s fighting from Joe’s white manager, Tom Moody. Joe and Moody’s girlfriend Lorna fall in love, but eventually Lorna rejects Joe. At the show’s climax, Joe fights and kills his opponent Lopez (Jaime Rogers) in the ring. Driving away from the venue in his Ferrari, Joe is also killed in a crash.

During September at the Fisher Theater in Detroit, the company now needed to rehearse during the day a totally different show to what was being performed at night. Sammy wrote in Why Me?, “Golden Boy occupied twenty-four hours out of every day. We’d do a show at night and the next day we’d be rehearsing lines right up until curtain time.” By the end of the month, the new show was just about ready to head to New York.

Opening Night

Opening night was 20th October, 1964. Beyond the fact that the entire company was utterly exhausted, one consequence of the weeks and weeks of additional rehearsal throughout tryouts was an impact on Sammy’s voice (he appeared in 11 of the show’s 16 numbers, a massive load). In Detroit, he had suffered from severe hoarseness, and in previews in New York he was pushing through bouts of laryngitis. On opening night, however, any deficiency in Sammy’s singing was made up for by the overall energy of the production and the fearlessness of its central love story.

Despite the parlous state of Sammy’s voice, a cast recording was made several days after opening for Capitol Records, which had invested heavily in the production in exchange for the rights to the cast album. (Davis re-recorded four songs six months later for a re-release when he was in better voice.) Capitol also had Nancy Wilson record “I Wanna Be With You”. Several orchestras and jazz ensembles recorded “Night Song” (as “The Theme from Golden Boy”), or released albums of the score, including Art Blakey, Quincy Jones, Sammy Kaye, Don Costa and H.B. Barnum.

The vital reaction from the New York critics was positive overall, despite some lingering issues. Joe and Lorna’s irrevocable need for one another is not displayed, just announced. Not all the songs, which had mostly only suffered minor lyric changes, made complete sense where they were placed in the final version. The audience was left with questions like –why does Lorna sing “Lorna’s Here” to Tom when the audience already knows she doesn’t quite believe it? Why does she sing “I Wanna Be With You” to Joe, and then turn around in the next scene and renounce him? Such issues were never resolved.

Strouse and Adams’s ambitious urban-inspired score yielded several standouts (“Night Song”, “I Wanna Be With You”, and “While The City Sleeps”), but no commercial stand-alone hits. Despite this, it is considered by some to be their best score. Notably, the usual overture was eschewed in favour of a rhythm-based opening featuring the sounds of boxers punching bags, skipping ropes, shadow boxing and so on, which was considered one of the highlights of the show.

Strouse wrote about the score in 2002: “In a way, what I’m saying is Golden Boy may be a signal American musical because we wouldn’t/couldn’t write the ‘pop’ Sammy Cahn-Jimmy Van Heusen songs with the Sinatra overlay that Sammy could metamorphose into jazz-sounding phrases, and Sammy wouldn’t/couldn’t/didn’t sing our version of ‘black’. He was bursting to do jazz; I was fighting to carve the notes ‘just so’. We went against each other, which, as we all know, can end in love.”

Civil Rights Impact

Having a fully integrated company, and running at the height of the civil rights era, Golden Boy had significant cultural resonance. It was the first time in a long time that a Broadway audience had been confronted with real social and political frustration. Its big production number, “Don’t Forget 127th Street” was sarcastic, cynical, and mocked the Broadway trope of poor people being content with their lot, and loving the slum where they live.

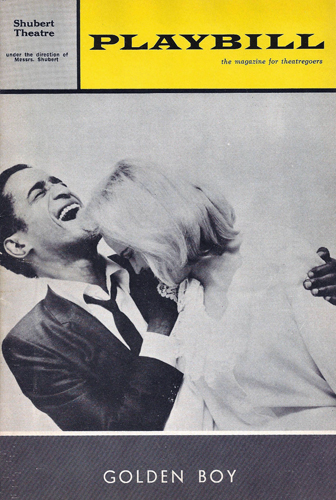

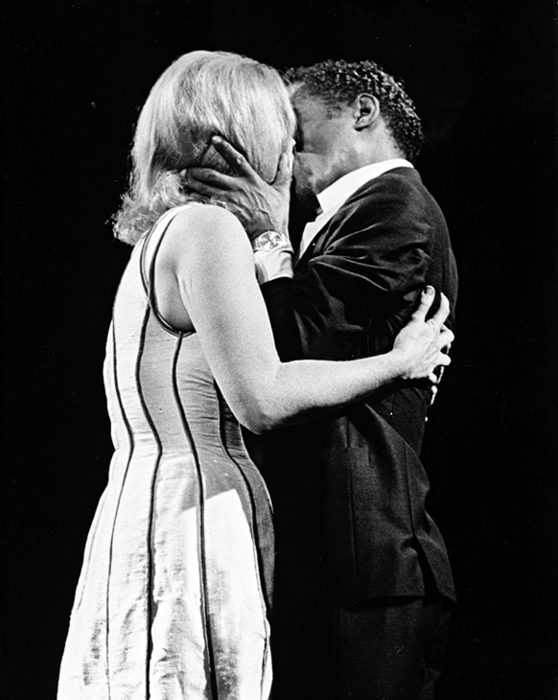

While the critics might have been happy, not everyone was pleased to see an interracial romance on stage in New York in 1964. The Act II kiss between Lorna and Joe had scandalised audiences during tryouts, and the show received numerous bomb and death threats right from its opening days in Philadelphia until its close on Broadway in March 1966. All the principal people in the production received bodyguard protection.

Paula Wayne recalled: “I never expected such hatred. I never expected such vitriolic things would be said to me. But Sammy did. He told me the only way to deal with hatred is not to dignify it. And he always stood by me.” On one occasion a klieg light blew out during a performance, sounding like gunshot. “We were in the middle of a love scene. Sammy spun me around to put his own back to the audience.”

In late March 1965, Sammy was given time off the show to participate in the Selma to Montgomery March, alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. The civil rights leader had already been to watch Golden Boy, and King is said to have been particularly drawn to the big gospel number “No More” (“I ain’t bowin’ down, No more!”). Sammy continued his work fundraising for civil rights causes during Golden Boy’s run, and in April, Hilly Elkins and Sammy produced and hosted a benefit show for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference called Broadway Answers Selma.

Tony Award Nomination

In late May 1965, Tony Award Nominations were announced. Golden Boy appeared in four categories, Best Musical, Best Producer (Musical) – Hillard Elkins, Best Choreography – Donald McKayle, and Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Musical – Sammy Davis, Jr. The Awards ceremony was held at The Astor Hotel on 13th June, but Golden Boy lost in all four categories to the respective nominations from Fiddler on the Roof.

For a brief period of 1965, Sammy dialled back on the publicity and the various extra-curricular activities that had kept the Golden Boy company together, and spent more time with his family. He soon found this was not for him. “I got where I am by single-mindedness, by one hundred percent involvement: I ate, talked, breathed, slept, lived show business. Then I started phoning it in. I became a part time Sammy Davis, Jr. It was insanity.”

His subsequent renewed focus on work saw him film a movie (A Man Called Adam), publish and promote an autobiography (Yes I Can) and host a weekly one-hour variety TV show (The Sammy Davis, Jr. Show on NBC), all while performing 8 shows a week on the stage. The workload contributed to the breakdown of his marriage with May Britt. Sammy and May separated toward the end of Golden Boy’s run.

With his marriage in terminal trouble and his TV show cancelled, Sammy felt a need to return to the road. His contract with Elkins didn’t expire until 1967, so the two agreed to a future London-based production of Golden Boy, and closed the show on 5th March, 1966. With the extended preparatory work writing the show, the craziness during tryouts, and the additional security demanded by the subject matter, Golden Boy made Broadway history as the longest-running show to lose money.

MUSICAL NUMBERS

1. Workout – Boxers

2. Night Song – Joe

3. Everything’s Great – Tom, Lorna

4. Gimme Some – Joe, Terry

5. Stick Around – Joe

6. Don’t Forget 127th Street – Joe, Ronnie, Company

7. Lorna’s Here – Lorna

8. The Road Tour – Joe, Lorna, Tom, Roxy, Eddie, Tokio, Company

9. This Is the Life – Eddie, Joe, Lola, Company

ACT 2

10. Golden Boy – Lorna

11. While the City Sleeps – Eddie (Dance trio: Mabel, Lopez, Les)

12. Colourful – Joe

13. I Want To Be With You – Joe, Lorna

14. Can’t You See It? – Joe

15. No More – Joe, Company

16. The Fight – Joe, Lopez